Women in astronomy who reached for the stars

The United Nations have adopted two International Days in order to promote the full and equal access and participation of women in science and focus on women’s rights: the International Day of Women and Girls in Science on 11 February and the International Women’s Day on 8 March. The International Astronomical Union (IAU) through “The Women and Girls in Astronomy” project supports events that recognise the role of all women in advancing science and encourages everyone on and off the gender spectrum to consider careers in astronomy.

Starting from ancient Greece, we recall the names of women such as Theano, Aglaoniki and Hypatia, who were astronomers, mathematicians and philosophers of their time. Theano came from the Thurians of southern Italy. She belonged to the Pythagorean school and is considered the most famous female astronomer and cosmologist of ancient times. Aglaonice, originally from Thessaly, is mentioned by Plutarch for her ability to predict solar eclipses. Nowadays, a crater in the southern hemisphere of Venus bears her name in honor of the astronomer. Hypatia of Alexandria was a Neoplatonic philosopher. She was involved in works of geometry, algebra and astronomy, as well as the construction of scientific instruments such as the astrolabe. Her end was tragic, unjust and violent, as she was murdered by a fanatical mob because of her gender and her interest in science.

This tribute cannot include the enormous work and contribution of all women in Astronomy and Astrophysics. We will selectively focus on some of the important women of the last centuries who have contributed to the development of Astronomy and Astrophysics through their work. A minimum tribute to the scientists who, despite the difficulties, obstacles and discrimination they faced, as the position of women in science was not fully accepted, laid the foundations on which great astrophysicists of modern history were built.

A brief historical review

Our review begins in the 16th century with Sophia Brahe (1556–1643), the sister of renowned astronomer Tycho Brahe. At the age of 17, she began assisting her brother with astronomical observations, contributing to a project that later formed the foundation for Sir Isaac Newton’s predictions of planetary orbits. Although Tycho refused to train her in astronomy, Sophia pursued the subject independently, teaching herself through German books and translating Latin texts at her own expense. In addition to astronomy, she studied gardening and chemistry under her brother’s guidance. However, as her career progressed, Tycho discouraged her from furthering her research in astronomy, believing it to be too complex for a woman. Despite this, he acknowledged her “determined mind” with admiration.

Figure 1: Sophia Brahe (credit: Wikipedia, public domain)

The 17th century is characterized by very important figures in the field of astronomy. Maria Cunitz (1610-1664) was a successful astronomer from Silesia and the most remarkable female astronomer of the early modern era. She wrote Urania propitia (1650), in which she provided a simpler functional solution to Kepler’s second law for determining the position of a planet in its elliptical orbit. In her honor, the Cunitz crater on Venus and the dwarf planet 12624 Mariacunitia have been named after her.

The French astronomer Jeanne Dumée (1660–1706) published a summary of the arguments supporting Copernicus’ heliocentric theory in 1680, titled “Entretiens sur l’opinion de Copernic touchant la mobilité de la Terre” (Conversations on Copernicus’ Opinion on the Movement of the Earth). She was also known for her feminist views, advocating that women were just as intelligent and capable as men in the scientific world. She wrote that “between a woman’s brain and a man’s brain there is no difference“. In her writings she included an apology for writing about a subject that was considered, at the time, “too delicate a task for people of her sex”. Through her dedication to astronomy, she sought to inspire other women who doubted their own abilities, aiming to convince them that there was no inherent difference between men and women in their capacity to pursue science.

Shortly afterwards, in 1690, Elisabetha Koopman Hevelius (1647-1693), widow of Johannes Hevelius, whom she had assisted with his observations (and probably his calculations) for over twenty years, published under her husband’s name the work “Prodromus Astronomiae“, the largest and most accurate astronomical catalogue up to date! The collaboration between Elisabetha and Johannes is attested to by two surviving documents depicting Hevelius looking at the sky with his wife.

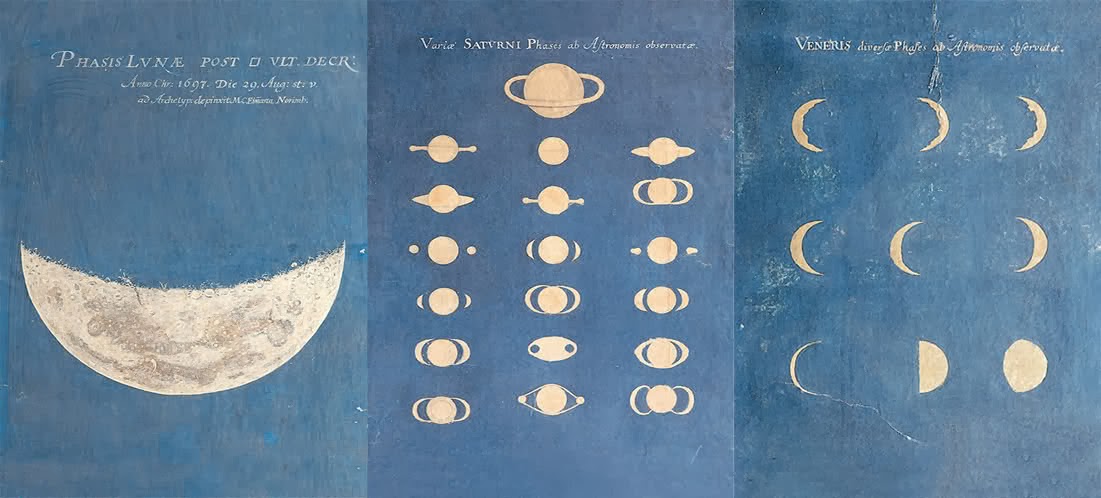

Figure 2: Astronomical illustrations by Maria Clara Eimmart. (credit: Wikipedia, public domain)

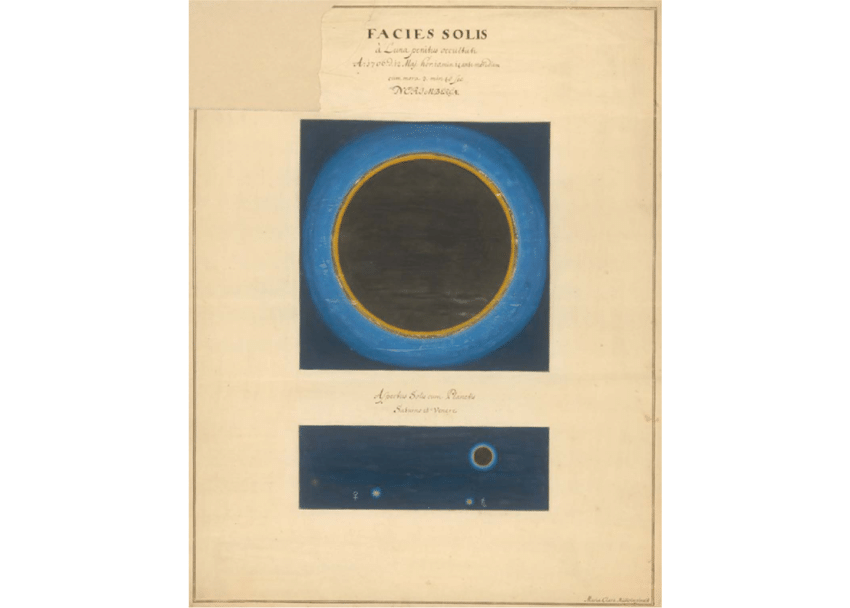

Figure 3: Two illustrations depicting the total solar eclipse of May 12th, 1706, by Maria Clara Eimmart, in Nürnberg (Nuremberg) (adopted from MS SBB Kart A2398; Courtesy of Ó Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Kartenabteilung. Credit: Hayakawa, Graphical Evidence for the Solar Coronal Structure during the Maunder Minimum: Comparative Study of the Total Eclipse Drawings in 1706 and 1715, J. Space Weather Space Clim. 2021, 11, 1, DOI:10.1051/swsc/2020035)

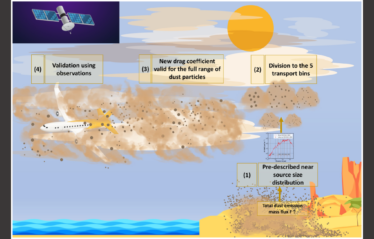

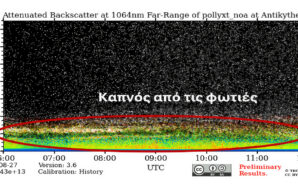

At the end of the 17th century, the German astronomer and engraver Maria Clara Eimmart (1676-1707) drew more than 350 detailed drawings of the phases of the moon. Eimmart’s continuous series of illustrations formed the basis for a new lunar map. Thanks to her father, she received a general knowledge of French, Latin, mathematics, astronomy, drawing and engraving. Her skills as an engraver allowed her to assist her father in his work. She became known for her depictions of the phases of the moon. It was not until 2012 that two of her paintings were found, depicting the total solar eclipse observed in Nuremberg in 1706. These paintings are in excellent agreement with descriptions of the phenomenon. They are of considerable scientific importance, as they are a unique depiction of the solar corona, made by a trained astronomer during the Maunder Minimum. The Maunder Minimum (1645-1715) is a period of low solar activity, with solar phenomena appearing particularly weak. During this period of minimum solar activity, the Northern Hemisphere experienced exceptionally low temperatures. Lakes and rivers froze, and snow remained for a long time without melting. even at relatively low altitudes.

At the beginning of the 18th century, the German astronomer Maria Kirch (1670 – 1720), becomes the first woman to discover a comet, the so-called “Comet of 1702” (C/1702 H1). Her close associate, Johann Gottfried Galle, claimed the discovery as his. It wasn’t until 1710 that he admitted the truth. In 1707 Kirch published her observations of the aurora borealis and in 1709 a paper on an upcoming conjunction of the Sun, Saturn and Venus, which took place in 1712. In 1712 she published another paper about the 1714 conjunction of Jupiter and Saturn.

We continue with the self-taught Chinese astronomer Wang Zhenyi (1787-1797), who published at least a dozen books and many articles on astronomy and mathematics. She constructed a famous scientific exhibit that accurately simulated a lunar eclipse using a lamp, a mirror and a table. Her love of knowledge and education in astronomy, mathematics, geography and medicine led her to break the customs of the time, which limited women’s rights.

Figure 4: Wang Zhenyi (credit: https://scientificwomen.net/women/zhenyi-wang-98)

Near the end of the 18th century, the French astronomer Louise du Pierry (1746-1807), became the first woman professor at the University of Sorbonne in Paris and lead the first course addressed to women (Cours d’astronomie ouvert pour les dames et mis à leur portée). She published many works on the collection of astronomical data.

As we reach the 19th century, we cannot fail to mention Mary Somerville and Caroline Herschel, who were elected as the first women members of the Royal Astronomical Society, in 1835.

The Scottish scientist and writer Mary Somerville (1780-1872) studied the relationship between light and magnetism, publishinga paper entitled “The magnetic properties of the violet rays of the solar spectrum” in the Proceedings of the Royal Society, in 1826. Although her conclusions were wrong, the study made her known to the scientific community. Her research also contributed to the creation of an early form of the optical spectrograph.

The German astronomer Caroline Herschel (1750-1848) contributed to astronomical research by discovering several comets, including comet 35P/Herschel-Rigollet, which bears her name. Caroline was the younger sister of the astronomer William Herschel, with whom she collaborated throughout her career.

In 1848, the American astronomer, librarian, naturalist and educator Maria Mitchell (1818-1889) won a gold medal for her discovery of comet 1847 VI. She was the first woman internationally to work as a professional astronomer and as a professor of astronomy, having accepted a position at Vassar College in 1865. She was also the first woman elected to membership in the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the American Association for the Advancement of Science. She states: “Until women throw off this reverence for [male] authority they will not develop. When they do this, when they come to truth through their investigations … their minds will work on and on, unfettered.”

In 1893-1894, astronomers Dorothea Klumpke and Margaretta Palmer became the first women to earned doctorates in astronomy from the University of Paris and Yale University, respectively. It would take another 30 years before another woman, Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin, earned a doctorate in astronomy from Radcliffe College.

In the 20th century, the renowned American astronomer Henrietta Swan Leavitt (1868–1921) made a groundbreaking discovery in 1912 by calculating the distances of Cepheid variable stars from Earth, a pioneering achievement for the time. A graduate of Radcliffe College, Leavitt worked at the Harvard College Observatory, where she analyzed photographic plates to measure stellar brightness and compile star catalogs. She discovered the period-luminosity relationship of variable Cepheid stars, contributing to the accurate measurement of distances in astronomy. Her work enabled the calculation of distances up to 20 million light-years from Earth, providing crucial insights into the scale of the Milky Way. After her death, astronomer Edwin Hubble relied on this relationship to prove that the universe was expanding.

Figure 5: Henrietta Swan Leavitt (credit: Wikipedia, public domain) |

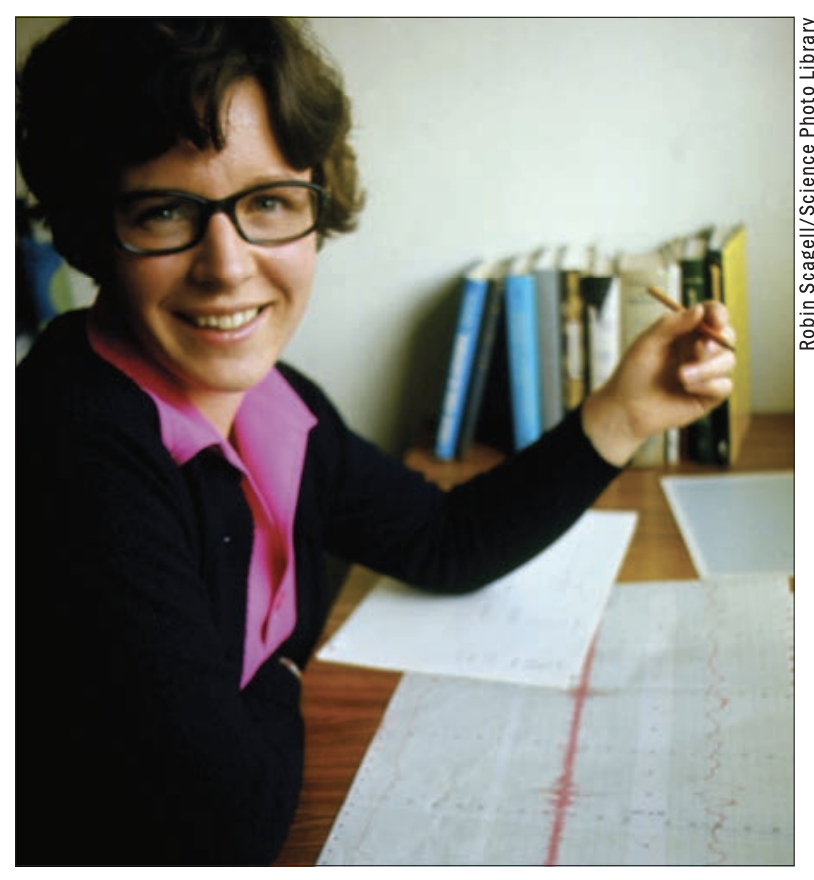

Figure 6: Jocelyn Bell Burnell (credit: Science Photo Library) |

In 1981, Vera C. Rubin (1928-2016) became the second female astronomer elected to the National Academy of Sciences. She began as the only undergraduate astronomy student at Vassar College in the USA and went on to graduate studies at Cornell and Georgetown Universities in the USA. Studying the rotation curves of galaxies, she revealed a discrepancy between their theoretical and observed motion, providing strong evidence for the existence of dark matter. Although initially met with scepticism, her work was confirmed and changed our understanding of the universe. In her honour, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile was named after her.

In 2018, Jocelyn Bell Burnell received the special Breakthrough Prize in Fundamental Physics for her scientific achievements and “inspirational leadership”. She donated all of the prize money to create scholarships to help women, underrepresented minorities, and refugees pursuing physics degrees. Burnell, born in 1943, is an astrophysicist from Northern Ireland. As a graduate student, she discovered the first radio pulsars in 1967. This groundbreaking discovery ultimately led to Anthony Hewish, her PhD supervisor, and his colleague Martin Ryle being awarded the 1974 Nobel Prize in Physics; however, Burnell was not among the recipients.

In 2020, Andrea Mia Ghez will become only the fourth woman to receive the Nobel Prize. Born in 1965, Ghez is an American astronomer and professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy at the University of California, Los Angeles. Her research focuses on the center of the Milky Way galaxy. The 2020 Nobel Prize was awarded, in part, to Ghez and Genzel for their discovery of a supermassive massive object, the black hole at the center of the Milky Way. It is worth noting that between 1901 and 2024, 5 women have received a Nobel Prize in Physics as opposed to 222 men, representing a mere ~2%.

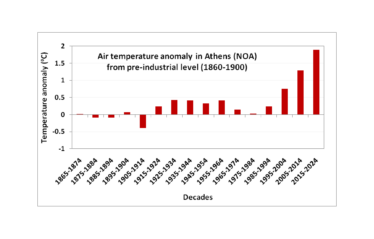

Modern data

In recent decades, women have become increasingly involved in astronomy and science, enjoying significantly greater opportunities than in the past. However, working women—including those in astronomy—continue to encounter challenges and discrimination in their careers and daily lives. According to the European Commission (2020), no EU Member State has yet achieved full gender equality, as progress remains slow, and disparities persist in employment, wages, caregiving responsibilities, and pensions. On average, women in the EU earn 13% less than men (Figure 1) and continue to face obstacles in entering and sustaining their careers. Factors such as lower wages, higher rates of part-time employment, and career interruptions due to caregiving responsibilities further contribute to the gender pension gap. Notably, Greece ranks last among EU countries in terms of gender equality, while Sweden holds the top position.

Graph 1: Statistics from the EU.

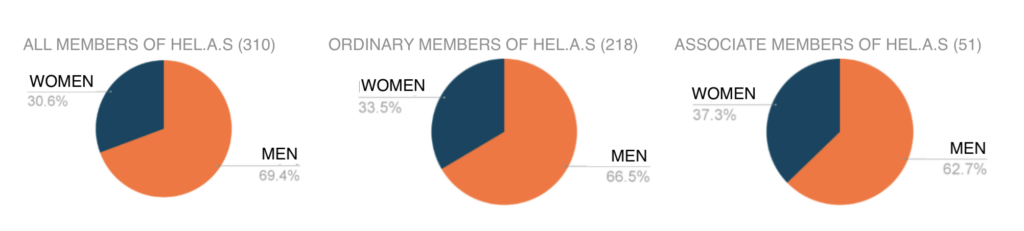

Regarding Greek women astronomers, data from the Hellenic Astronomical Society (Hel.A.S) for 2025 shows that only approximately 30% of its 310 active members are women. A detailed breakdown of these statistics is presented in Graph 2. We extend our gratitude to Professor Maria Petropoulou for providing the membership data of Hel.A.S. Despite their underrepresentation, Greek women astronomers have made remarkable contributions across all fields of astronomical research on an international level. In our next article, we will explore the achievements of contemporary Greek female astronomers and their impact on global research.

Graph 2: Statistics from the Hellenic Astronomical Society (Hel.A.S – 2025).

The International Astronomical Union contributes to the strengthening of women in science, considering that dates such as 11 February (Women in Science Day) and 8 March (Women’s Day) can be the starting point for the implementation of actions and events aimed at motivating women, but also all citizens, to pursue a career in astronomy and science. Actions in the context of women’s contribution to the development and progress of astronomy will be carried out throughout the year. As 2025 is the year in which our Sun is heading towards its maximum activity, emphasis will be placed on solar physics and the phenomena of the Sun’s interaction with our Earth.

Stay tuned by following us and on social networks to be informed about and participate in our activities:

https://www.facebook.com/IAUNOCsGR

https://www.facebook.com/groups/2035400620214451/

Figure 7: Some of the women in science at the Institute for Astronomy, Astrophysics Space Applications and Remote Sensing of the National Observatory of Athens in Greece (February 2025)

Information about the authors of the article:

Dr. Fiori-Anastasia Metallinou is an astrophysicist at the Institute of Astronomy, Astrophysics, Space Applications and Remote Sensing of the National Observatory of Athens, head of the Thission Visitor Center and member of the National Outreach Coordinator (NOC) team for Greece of the International Astronomical Union (IAU).

Dr. Eleni Vardoulaki is an astrophysicist at the Institute of Astronomy, Astrophysics, Space Applications and Remote Sensing of the National Observatory of Athens, Member of the National Astronomy Educator Coordinator NAEC-GR of the Office of Astronomy for Education of the International Astronomical Union (IAU) and the PI of the the RADIIO educational programme funded by the Office of Astronomy for Development of the IAU.

Credits:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sophia_Brahe

https://scientificwomen.net/women/brahe-sophia-19

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jeanne_Dumée

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maria_Cunitz

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elisabeth_Hevelius

https://wilanow-palac.pl/en/knowledge/elisabetha-koopman-hevelius

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maria_Clara_Eimmart

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maunder_Minimum

https://scientificwomen.net/women/eimmart-maria-clara-168

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maria_Margaretha_Kirch

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Maria-Kirch

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wang_Zhenyi_(astronomer)

https://scientificwomen.net/women/zhenyi-wang-98

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louise_du_Pierry

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Somerville

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Caroline_Herschel

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_Astronomical_Society

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maria_Mitchell

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-05458-6

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Margaretta_Palmer

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henrietta_Swan_Leavitt

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vera_Rubin

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jocelyn_Bell_Burnell

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/2058-7058/30/9/35

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Andrea_M._Ghez

https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/lists/all-nobel-prizes-in-physics/

https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/statement_23_5692

https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Gender_pay_gap_statistics

Further reading:

“The women who opened the doors to astronomy”

“The COVID-19 pandemic reinforced gender inequalities as women took on more of the intensified informal care and housework demands”

“COVID‐19 and the gender gap in work hours”

https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7361447/

“Gender Pay Gap in the EU remains at 13% on Equal Pay Day” https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/statement_23_5692

“The gender pay gap situation in the EU”